Life in Grottole is shaped less by schedules and more by habit. It is a small, hilltop village in southern Italy where daily routines have changed slowly over generations and where people still organize their days around work, weather, and relationships rather than plans or programs.

Mornings begin early. Light hits the stone buildings and narrow streets, and the first sounds are practical ones: doors opening, footsteps on the street, and the familiar noise of Ape trucks moving through the village on their way to gardens, fields, or storage spaces outside town. Coffee is made at home, or taken standing at the local bar, often accompanied by a few words exchanged about the weather, the garden, or what needs to be done that day.

The village bar functions less as a destination and more as a pause point. People stop briefly, greet one another, share a comment or two, and move on. Conversations are short and repeated daily, building familiarity over time rather than through long gatherings. There is no rush, but there is also no performance—life continues as it always has.

Food is central to daily life, not as a culinary statement, but as routine. Many families maintain small plots of land in the surrounding countryside, known locally as campagna, where they grow vegetables, olives, and grapes primarily for home use. Meals are shaped by what is in season and what is available, with preservation—canning, curing, storing—still part of the yearly cycle. Much of what is eaten comes directly from these gardens, not by design, but by continuity.

Agricultural work remains woven into everyday life. Olive groves and vineyards surround the village, and tending them is often shared among family members. Time spent in the fields is as much social as it is practical, with exchanges of advice, complaints about weather, and comparisons of yields forming part of daily conversation. These shared routines quietly reinforce community bonds.

Social life in Grottole is informal and frequent rather than organized. People spend time outdoors, sitting, walking, or standing in conversation. Festivals and religious events still exist, but they are part of the village calendar, not staged attractions. Participation is assumed rather than advertised, and gatherings feel inward-facing, shaped by familiarity rather than novelty.

Intergenerational presence is visible throughout the village. Older residents remain active in daily life, passing on knowledge through example rather than instruction. Children move freely through the streets, learning how the village works by watching and participating. History here is not taught formally; it is absorbed through repetition and proximity.

Life in Grottole is not defined by spectacle or nostalgia. It is built from ordinary actions repeated over time—walking the same streets, tending the same land, sharing brief conversations day after day. For those who spend enough time here, these routines reveal a way of life grounded in continuity, responsibility, and belonging.

Daily Life

This site is intended to provide context about life in Grottole, not to plan visits or promote experiences.

Food and Seasonal Preparation

In Grottole, food is closely tied to season, land, and preparation rather than to choice or variety. What is eaten throughout the year reflects what is grown locally and what has been preserved from earlier months. The rhythm of food here is shaped less by preference than by timing.

Spring marks the beginning of the growing year. Gardens and fields are planted with vegetables intended primarily for household use rather than sale. Fava beans, tomatoes, peppers, zucchini, and other staples are sown with the understanding that much of what grows will later be preserved. Meals during this time are simple and closely tied to what is available fresh.

Summer is the most demanding period. Gardens require daily attention, and harvests begin to arrive in volume. Tomatoes are cooked down into passata and bottled for use throughout the year. Peppers are dried or preserved in oil, often strung and hung outside homes. These tasks are repetitive and time-consuming, frequently done in groups, with knowledge passed through observation rather than instruction.

Autumn brings a shift from vegetables to fruit and oil. Grapes are harvested and made into wine for household use, often in cantinas that have served this purpose for generations. Olives are collected by hand and taken to the mill to be pressed into oil that will last until the following harvest. These moments are both practical and social, involving long days of shared labor and waiting.

Winter is a period of using what has been prepared. Dried legumes such as fava beans, preserved vegetables, cured sausages, and stored oil form the basis of daily meals. Food preparation continues indoors, quietly and steadily. Meals reflect restraint and continuity rather than abundance, shaped by what was preserved months earlier.

Throughout the year, food preparation in Grottole reinforces patience and foresight. Preservation is not treated as a hobby or revival, but as ordinary work that ensures continuity. Eating well here is less about novelty and more about familiarity—knowing where food came from, who prepared it, and how it fits into the larger cycle of the year.

Daily Shopping and Provisioning

Daily life in Grottole is shaped by frequent, small trips rather than large weekly shops. Most residents buy what they need as they need it, with shopping woven into regular routines instead of planned in advance. This approach keeps food fresh and naturally reinforces daily contact with familiar faces.

Meat is typically purchased from one of the village’s four macellerie, each with its own clientele, specialties, and rhythms. Cuts are chosen at the counter, often with advice offered, and quantities are modest—meals are usually planned day by day rather than for the entire week.

Fruit and vegetables are bought just as locally. There is a dedicated fruit and vegetable shop in town, along with small grocery stores that carry fresh produce alongside everyday essentials. Many residents also buy directly from a local woman who, together with her husband, grows an exceptional variety of vegetables and sells them informally within the village, depending on the season and availability.

In addition to these smaller shops, Grottole has three grocery stores that cover most everyday needs, including dry goods, dairy, household items, and fresh produce. These stores support daily shopping habits rather than bulk buying and are used interchangeably depending on proximity, timing, and routine.

Beyond food, the village also supports everyday practical needs. There is a ferramenta (hardware store) where locals pick up tools, small repair items, electrical supplies, and household fixes—often with advice included. A stationery shop provides school supplies, office items, cards, and basic printing needs, serving families and students alike. For larger projects, there is also a home and construction supply yard just outside the village, used for renovation materials and most construction-related needs.

For newcomers, this way of shopping often requires a shift in mindset. Rather than efficiency or consolidation, the emphasis is on freshness, familiarity, and repetition. Over time, daily shopping becomes less about errands and more about rhythm—small exchanges that quietly anchor each day within village life.

Making & Craft in Grottole

Work and craft have long been part of daily life in Grottole. Skills were passed down not as abstract traditions, but as practical knowledge tied to place, materials, and the need to make a living. Making here has always existed alongside farming and daily labor, shaped by necessity as much as by creativity.

Several practices visible in the village today—ceramics, honey, olive oil, and grain—reflect how tradition in Grottole continues through both continuity and adaptation.

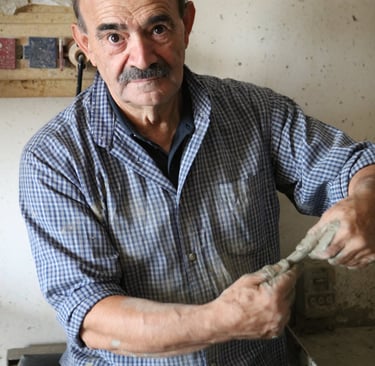

Ceramic making has deep roots in the village, shaped by local materials and everyday use. This tradition continues today through Nisio, a master potter, artist, and professor whose family has lived in Grottole for generations. He maintains a working studio in the village, as well as a second studio in the Sassi of Matera, linking Grottole’s living tradition to a wider historical and cultural landscape.

Nisio’s work reflects the reality of a practicing artisan. His studio includes a range of pieces: pottery made to support a livelihood, traditional forms rooted in daily use, and more personal artistic works developed through experimentation and expression. A simple walk through his studio shows this full spectrum. Among the most enduring pieces are traditional objects—plates, bowls, and vessels—finished with distinctive artistic treatments. These are items meant to be used in everyday life, continuing the close relationship between craft, food, and the kitchen.

Honey production represents a more recent chapter in Grottole’s working life, but one equally grounded in care, knowledge, and attention to place. The village has come to be known locally as a “city of honey,” in part due to the work of Rocco, a lifelong resident and village barber who is also a dedicated beekeeper. His involvement with bees is pursued with patience and genuine passion, alongside his daily life in the village.

Rocco’s beekeeping follows the landscape. His hives are rotated through different natural environments surrounding Grottole over the course of the year, following flowering cycles and seasonal changes. This allows each harvest to reflect specific moments in time, shaped by wildflowers, fields, and native growth rather than standardized production. Honey here becomes a record of season and terrain.

Olive oil follows a similar rhythm. Grottole has its own frantoio, where olives from the surrounding hills are pressed each season. During the harvest, the frantoio becomes a shared point of activity, with families bringing in olives gathered from their own trees and leaving with oil that reflects the year’s weather, soil, and care. Olive oil here is not branded or marketed; it is recognized by taste, origin, and the people who produced it.

Grain, too, shapes daily life. The fields surrounding the village are planted with wheat that is milled and used for locally made pasta, continuing a long cycle that connects agriculture, food, and everyday meals. Like olive oil, this is not production for display, but for use—quietly sustaining kitchens and tables through familiar, repeated practice.

Equally important across all of these crafts is the sharing of knowledge. Rocco regularly volunteers his time to teach school children about beekeeping, helping them understand the role of bees, the seasonal nature of the work, and the connection between agriculture and ecology. Teaching, in this sense, is not separate from the craft—it is part of how it continues.

What unites ceramics, honey, olive oil, and grain in Grottole is not the product, but the attitude toward making. These practices are sustained by people who are deeply engaged in their work and generous in sharing it, whether with local residents or with foreigners who take the time to learn. Knowledge here is not packaged or promoted; it is passed on through conversation, demonstration, and sustained interest.

In this way, craft in Grottole remains a living practice. It continues not because it is preserved, but because people care enough to adapt, to teach, and to keep working with their hands in ways that make sense within village life.